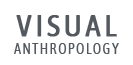

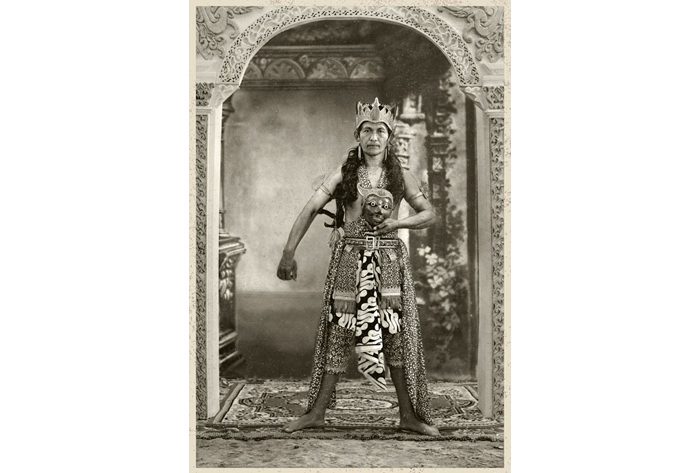

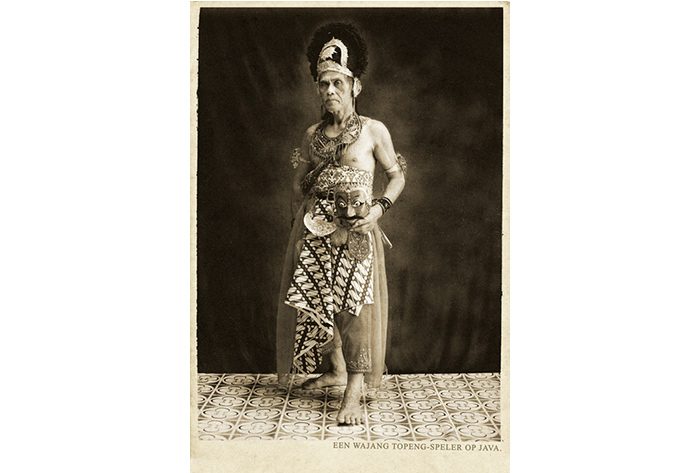

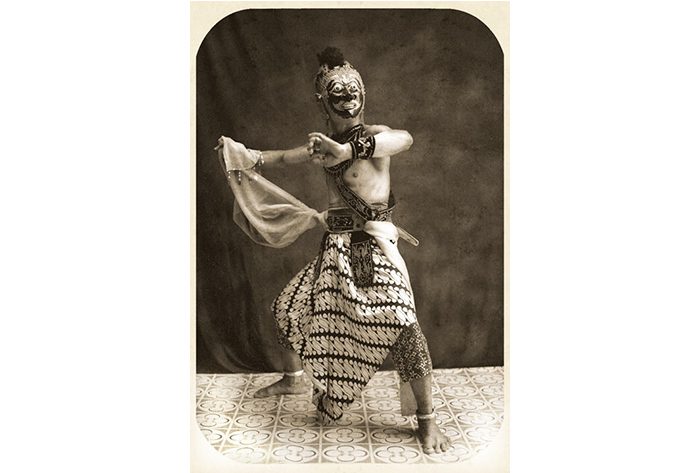

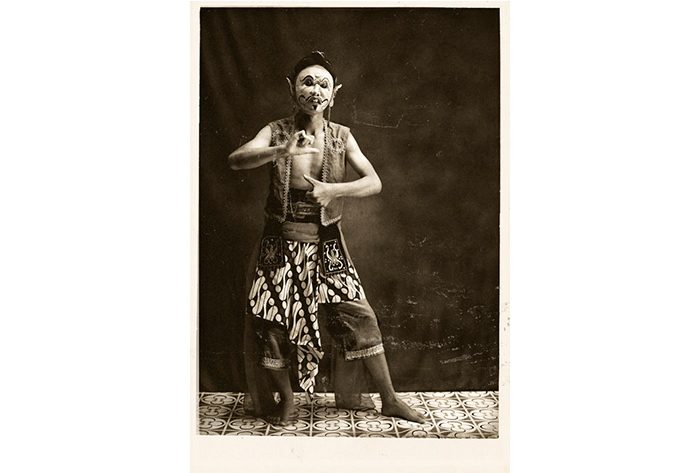

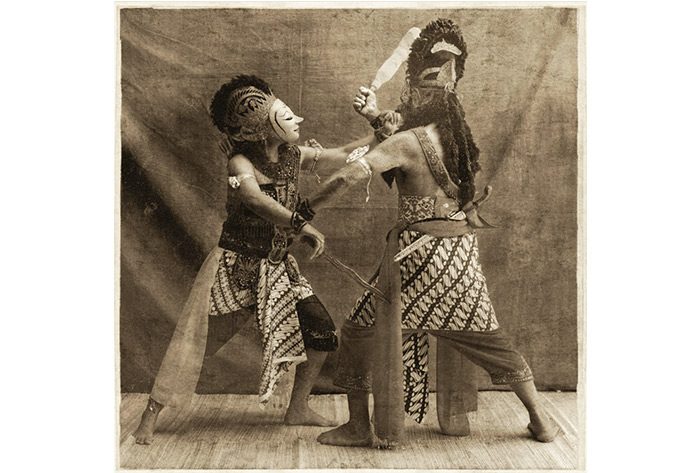

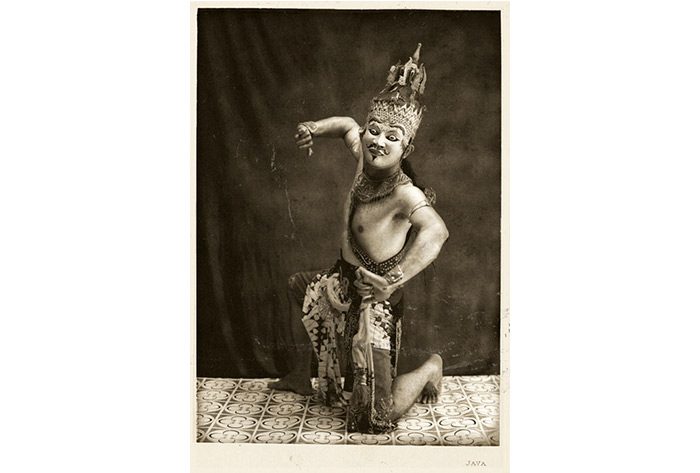

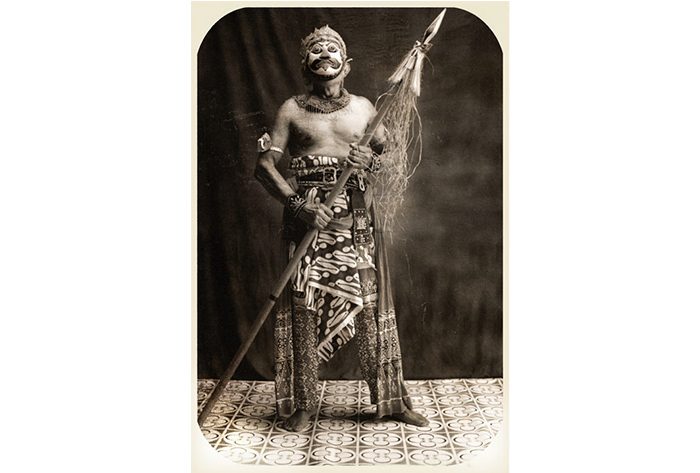

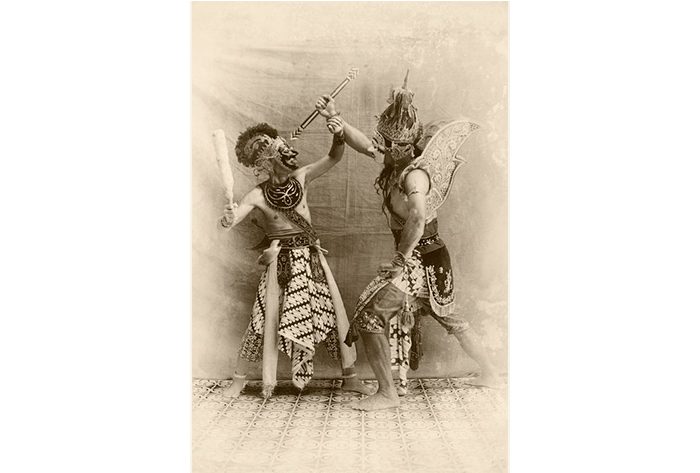

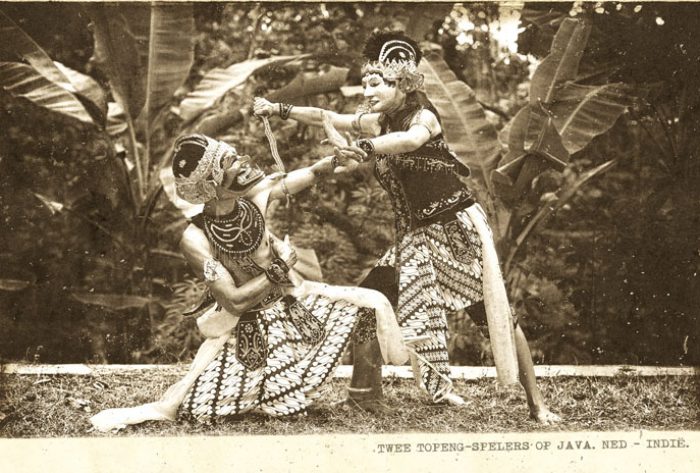

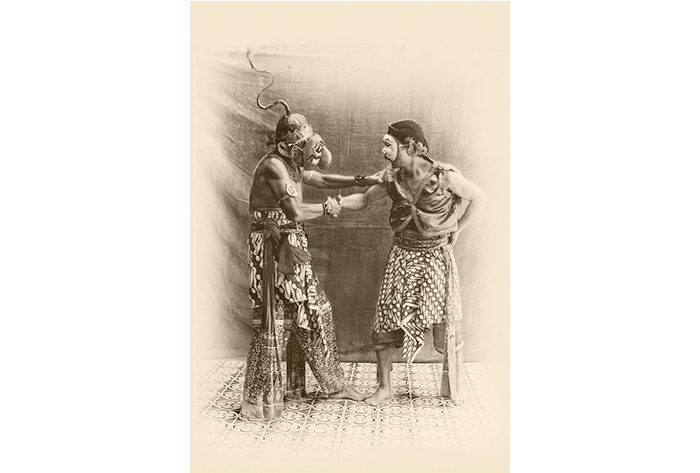

“The Last Breath Of The Prince”

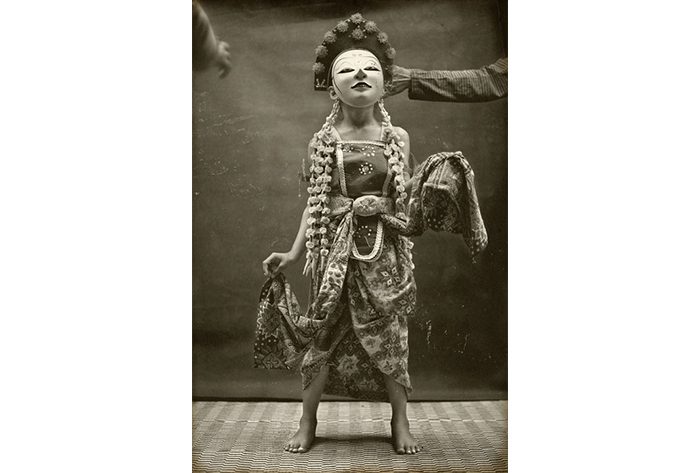

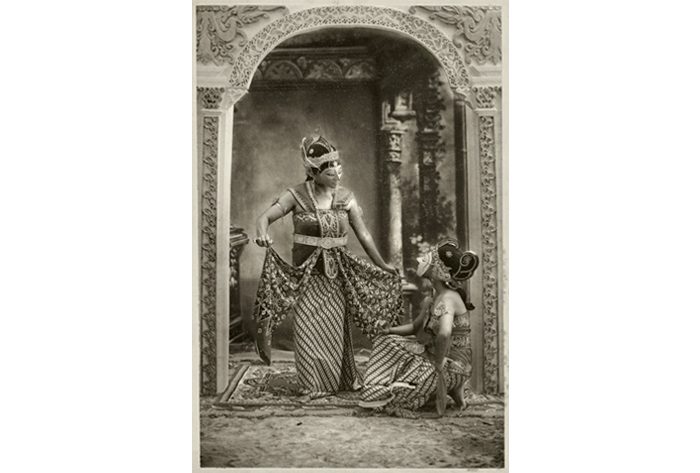

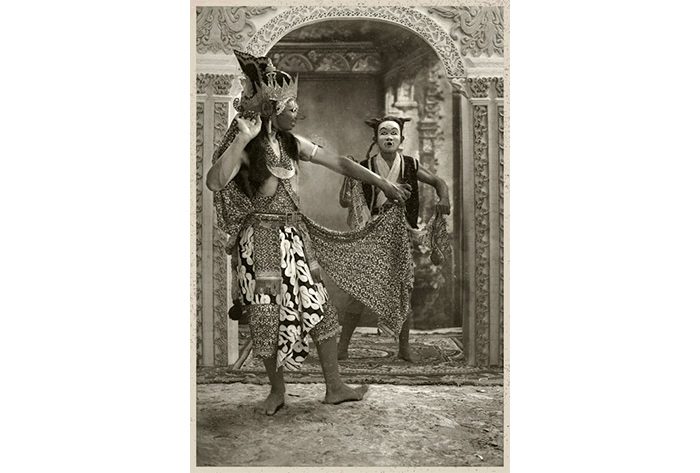

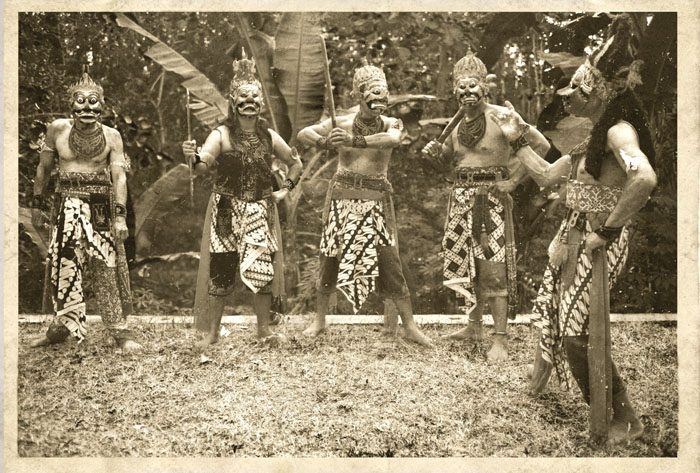

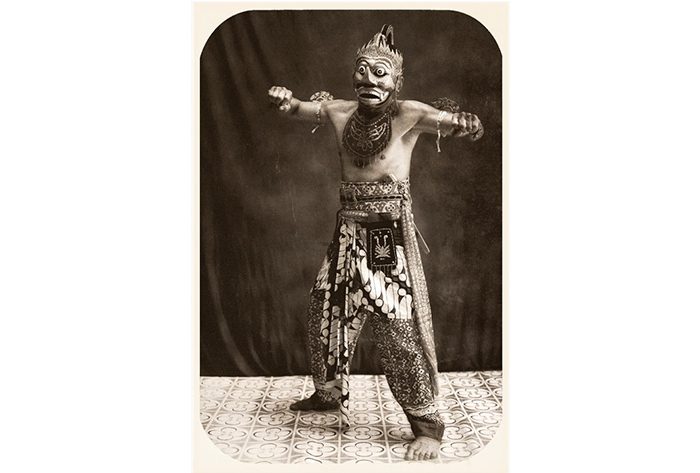

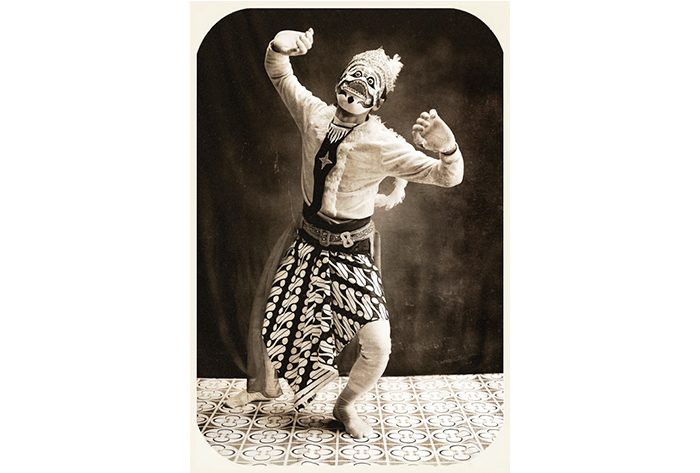

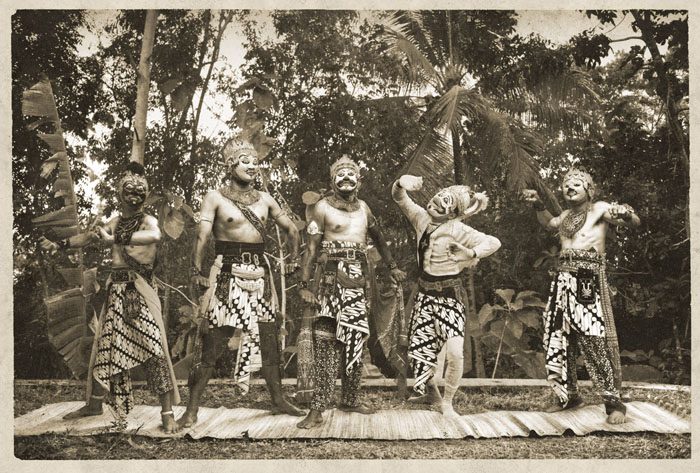

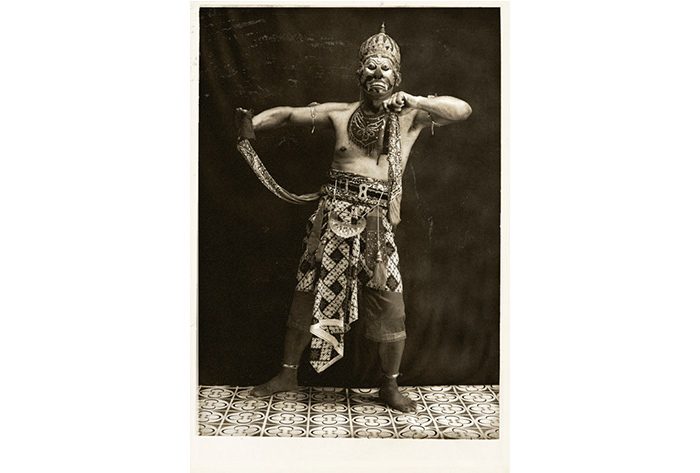

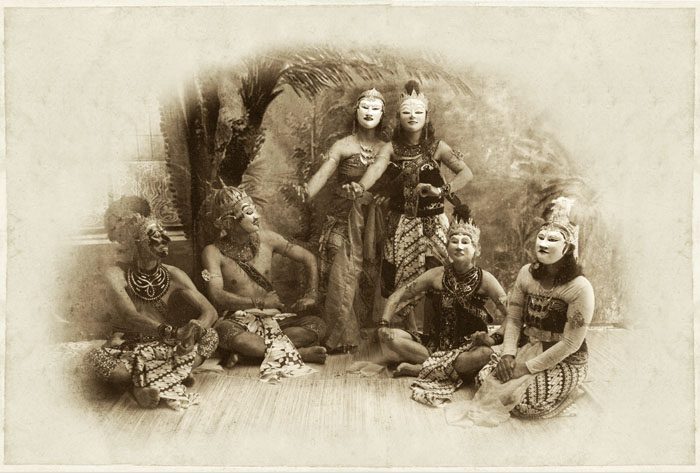

A story, through a masked dance performance, lives on in Java, with roots and elements originating from an ancient, pre-Hindu creation myth, and retold in the 21st century in ever fewer rural villages in East and Central Java. Prominent in the story and its multitude of characters are the sun and the moon elements, in many ways it reflects a moon myth, with motifs dealing with the beginning of new eras depicted by the rise and fall of great Javanese dynasties. Not a singular story, not hammered out in stone, the Panji Cycle as it is known, is virtually a vast and diverse mass of stories essential to its central theme.

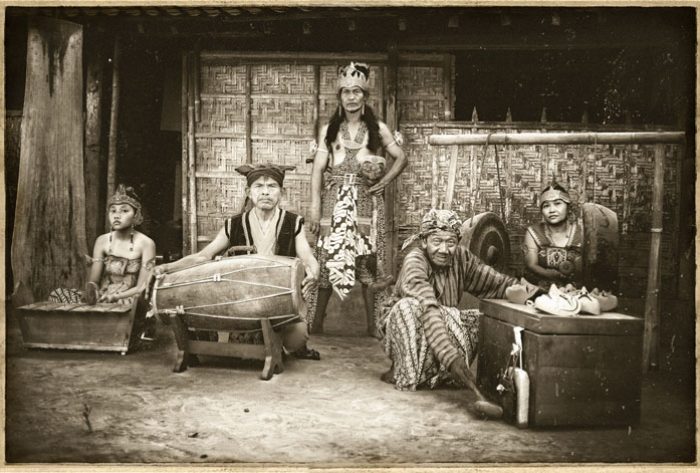

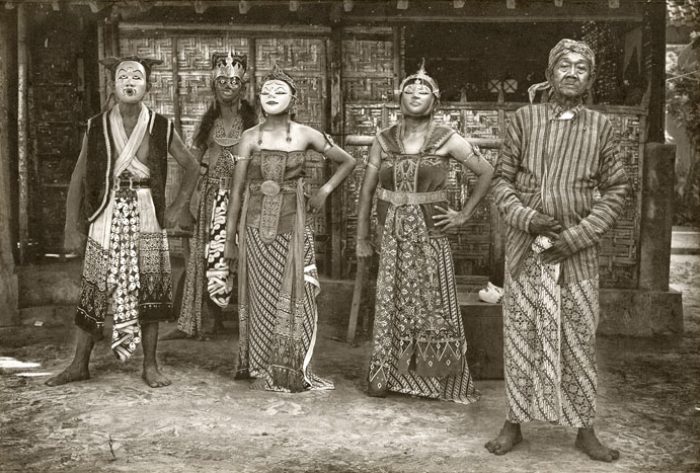

Sadly, the syncretism, once so characteristic of Javanese mysticism, is fading away rapidly in a modernizing Indonesia. The Panji mask dance is today still performed by small groups in the island. When the master of a craft or the keeper of the knowledge is gone, there is nothing but material traces and vague memories left behind, crumbling away with time; there is no way to recreate their deepest intangible history and state of existence.

It is already too late for hundreds, or more likely thousands, of such cultural manifestations around the world. For the few surviving traditions, the time is now to safeguard continuous evolution and interpretation of their ancient spiritual cultural heritage.

Decisive moment

Nowadays, I think we are in a “decisive moment” as modernity, technology is reaching everywhere, often a process associated with loss of identity and traditions. In South Asia we are in a crucial moment where this loss is happening, unfortunately forcing the last opportunity to see something that will not be present any longer in the coming 10 or 20 years.